The Decision That's Paralyzing You

Most writers don’t get stuck because they lack ideas...

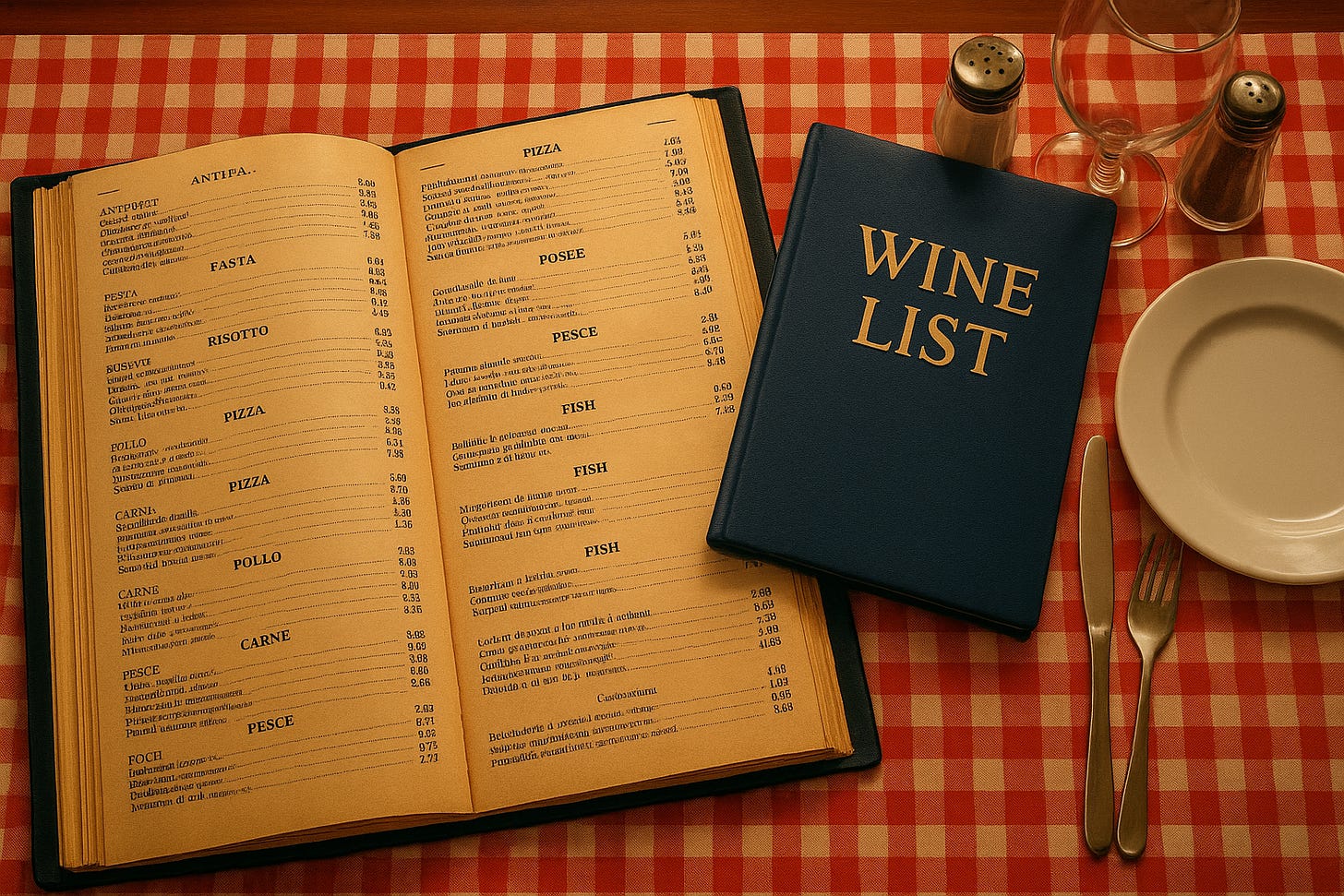

Nine pages!

Two for pasta, one for fish and seafood, another three just for pizza. I closed the menu halfway through, already overwhelmed.

"Here's also the wine list, sir", the waitress said, handing me something that looked more like a George R. R. Martin novel than a beverage selection.

I glanced at the exit, mildly entertaining the idea of slipping away while her back was turned.

My wife looks at the menu resting closed in front of me: "Do you know what to eat?"

To which I reply, "Honey, do you have an easier question?"

I don’t know about you, but if there’s one thing that gets me agitated, it’s confusion.

If I know where I’m going, I can find my rhythm. But when doubt creeps in—when the path forward feels uncertain—my mind starts spinning, restless until I can regain direction.

That menu, overflowing with options, is a fitting metaphor for what many writers face when they’re trying to get started online.

Do you launch a newsletter? Build a community? Use Twitter to grow an audience? Focus on essays? Offer paid subscriptions? Write every two weeks? Every day? What topics? Who’s it for?

And if you’re an overthinker like I am, you’ll spend days circling the options—changing your mind more times than Kanye West—and end up right back where you started: stuck.

But if you look closely, you’ll see there’s one core question buried underneath all the noise. It’s not always obvious, but it’s there driving the paralysis:

"Where am I REALLY going?"

You might not be consciously asking it, but it’s there, lurking behind every indecision.

And the more time you spend trying to solve it in your head, the heavier it becomes. Paradoxically, the more possibilities you imagine, the harder it is to act.

Rooting Imagination in Motion

Imagination is a powerful thing.

It took us to the moon, gave us Picasso’s Cubism, invented money out of thin air, transformed zeros and ones into the internet, and spun stories into entire belief systems.

But without boundaries, imagination can lose its ability to move us forward—and instead, leave us paralyzed.

It stretches the horizon so far that we lose our footing, overwhelmed by too many steps, too many unknowns.

We love to romanticize the myth of the lone genius struck by divine clarity. But Picasso didn’t wake up one morning and invent Cubism. Between 1901 and 1907, he moved through three distinct phases—Blue, Rose, and African-influenced—each one shaping his vision until he co-created the work that would come to define him.

He didn’t wait for the perfect idea. He created over 20,000 works in his lifetime—paintings, drawings, sculptures, ceramics.

As he famously said,

“Inspiration exists, but it has to find you working.”

So when asking “Where am I REALLY going?”, we need something that roots imagination in motion. A constraint that gives form to the fog.

Not a grand vision. Not a perfect plan. Just a small, clear starting point.

A way to move without needing to know everything. A way to begin, without being swallowed by the scale of the thing.

And while this idea might feel abstract, there’s a simple framework—borrowed from the world of startups—that can help.

It was designed for moments exactly like this: when the vision is blurry, the path uncertain, and the questions feel endless.

It’s called the Minimum Viable Product.

MVP

Imagine you want to open a bakery. You have big dreams: 20 kinds of cakes, fancy packaging, online orders, and a cozy café with jazz music and great lighting.

But before you spend months and tons of money building all that, you ask: “What’s the simplest version of this business I can launch to see if people even want my cakes?”

So instead of opening the full bakery, you:

Bake just one kind of cake (your best recipe).

Sell it at a farmers’ market.

Watch what happens.

That’s an MVP.

It’s not the full vision — but it’s the smallest, fastest, and cheapest version of your idea that lets you:

Test if people care

Learn what works (and what doesn’t)

Adjust before you go all-in

In startup terms, an MVP is:

“The simplest product you can build that still delivers value — and lets you learn.”

Airbnb started by renting the founders' apartment. Facebook began as a Harvard-only student directory. Zappos launched with photos of shoes from local stores, before even holding inventory.

The MVP lets you move forward without being crushed by the weight of perfection.

And its principles work just as well in creative projects—especially writing.

Minimal Viable Writing

The trouble with asking “Where am I REALLY going?” is that it rarely travels alone. Hot on its heels comes its anxious cousin:

"But what if I'm wrong?"

And just like that, you're caught in a loop—chasing the perfect beginning that never arrives.

But if you borrow the MVP lens and apply it to your writing (MVW), you remove the pressure to be right from the start.

You stop asking, “What’s the perfect thing to build?” and begin asking, “What’s the smallest thing I can test to learn what’s right for me?

Minimal Viable Writing clears the clutter. It strips away the noise and the paralysis of perfectionism, and invites you to focus on just three core things:

1. Hypothesis:

The hypothesis is what drives the whole experimentation. It's what will lead you to learn something about your writing at the end of it.

For people who are just getting started, the most important questions are often internal rather than external.

It's less about "will people read this?", and more about "What do I REALLY want to write about?"

So you don't need to overthink or overcomplicate things.

Just pick one to three themes or ideas you feel drawn to—curiosities, recurring thoughts, questions you can't stop thinking about, and go for it.

Remember: you're not entering a lifelong commitment here.

You're simply choosing a direction for a short-term experiment—enough to get started, and let clarity emerge through the work.

2. Plan of Action

Now, give yourself guardrails.

You’re not building an audience across six platforms. You’re not optimizing thumbnails or crafting the perfect content strategy. You’re simply writing.

To keep your momentum steady—and your expectations clear—you’ll want to set a few basic boundaries for your MVW:

Pick ONE platform:

Choose a place to publish your work. Don’t worry about the audience just yet—what matters is having a simple, accessible space to hit “publish.” Substack, Medium, a personal blog—all valid options.Set the experiment length:

Pick a timeframe that’s long enough to learn, but short enough not to feel overwhelming. Three months tends to work well—it gives you space to explore, but also a clear end point to reflect and recalibrate.Block off minimum daily time:

This is your non-negotiable. Write for at least 10 minutes a day—no matter what. That small commitment lowers resistance, keeps the creative muscles engaged, and makes room for momentum to build naturally. On busy days, 10 minutes is enough to maintain the rhythm. When life gives you margin, those few minutes often grow into hours of deep, uninterrupted writing.

3. Tracking

As you go along the MVW experiment, take notes of how you're feeling.

Are you enjoying writing about these ideas? Do you feel like there’s more to explore?

Which formats feel most natural?

Did you run out of space—or struggle to fill it?

Is this publishing cadence sustainable?

Reflect on these questions. Write your thoughts down. And resist the urge to pivot midstream—let the full experiment play out.

You’re not locking yourself into anything long-term. You’re gathering the insight you’ll need to make your next move with more clarity and confidence.

Clarity Comes After the First Step

You don’t need to have it all figured out. You don’t need the perfect niche, the right strategy, or a five-year plan.

Because clarity isn’t a prerequisite for action. It’s a result of it.

So pick your hypothesis. Make a little plan. And start your Minimal Viable Writing experiment.

The act of showing up is what helps shape the vision. As the rhythm of writing takes hold, it starts to clarify what truly matters. And through repetition, patterns begin to emerge: the ideas that stick, the ones that fade, and the ones you want to explore next.

It creates just enough structure to begin asking better questions. To shift your energy from “What if I get it wrong?” to “What might I discover if I keep going?”

And if you can do that, even for a short while, you’ll already be ahead of most people—still staring at the menu, still waiting for certainty—hoping the perfect path will reveal itself.

But it won’t.

The path doesn’t appear before you start walking.

The journey is what gives the path its shape.