The Invisible Path to Visible Work

What feels like failure is often the seed of a writer’s voice.

In the late 1980s, George Saunders was a technical writer at an environmental engineering firm, drafting manuals on groundwater and hazardous waste. By day, fluorescent cubicles. By night, after his wife and daughters were asleep, he sat at the table to work on his short stories.

For nearly six years, he wrote with little recognition. But in those invisible years he was laying the groundwork of his craft — persistence was teaching him what no other teacher could.

The magazines weren’t calling, yet he kept showing up: late nights, weekends, scribbles between work and family life. No rejection, silence, or dismissive note was enough to stop him.

Over time, he moved from what he called “some version of a Hemingway imitation” to a voice that could hold absurdity and tenderness in the same breath.

Then, after years of hard work, the breakthrough came. In 1996, at 37, his first collection, CivilWarLand in Bad Decline, was published. Critics hailed him as a new literary force, and the book was nominated for the PEN/Hemingway Award. To outsiders, Saunders had “arrived overnight.” In truth, what looked sudden was the harvest of years spent writing in the dark — discovering a voice that only consistency could uncover.

The years that felt futile became the foundation.

From Zero to One

As writers, we dream vividly. We picture the mornings where we wake up full of focus, brew coffee, read a favorite author for an hour, and then sit down to write a masterpiece. The vision is so seductive, so natural, that it feels like nothing could fit our lives better than being a writer.

But reality is not so kind. Going from nada to something demands resilience.

You reach the end of a long, chaotic day, only to find the energy you thought you’d have is gone.

When you finally sit down, you expect inspiration to arrive—the words to flow from your mind to the page in a rush of brilliance. But the masterpiece you hold in your head dissolves in front of you, leaving only sentences that feel clumsy, half-formed, unworthy.

Still, you finish. You summon the courage to hit publish. And you can’t help but hope the piece will travel, to find readers who will recognize its value.

The next time you sit down, you imagine it will be easier. But the same confusion resurfaces again. And that’s when doubt starts to creep in: “Am I truly a writer?”

The internet gave us all a stage, a chance to share our work with the world. But it also sold us an illusion: that success can be quick, that one piece can change everything. We see writers like George Saunders with thousands of readers, but what we’re really seeing is the moment of recognition—not the long years of unseen effort that came before.

And then there are the endless promises:

“Build an audience in 90 days.”

“The formula top writers use to craft masterpieces in minutes.”

“7 prompts to never run out of inspiration again.”

They sound alluring, and even if you know they’re false, they still whisper in the back of your mind, making you second-guess what deep down you already know:

That for any work to gain momentum, it must first endure a foundational phase. That to arrive, you can’t skip the humbling, invisible work of going from zero to one.

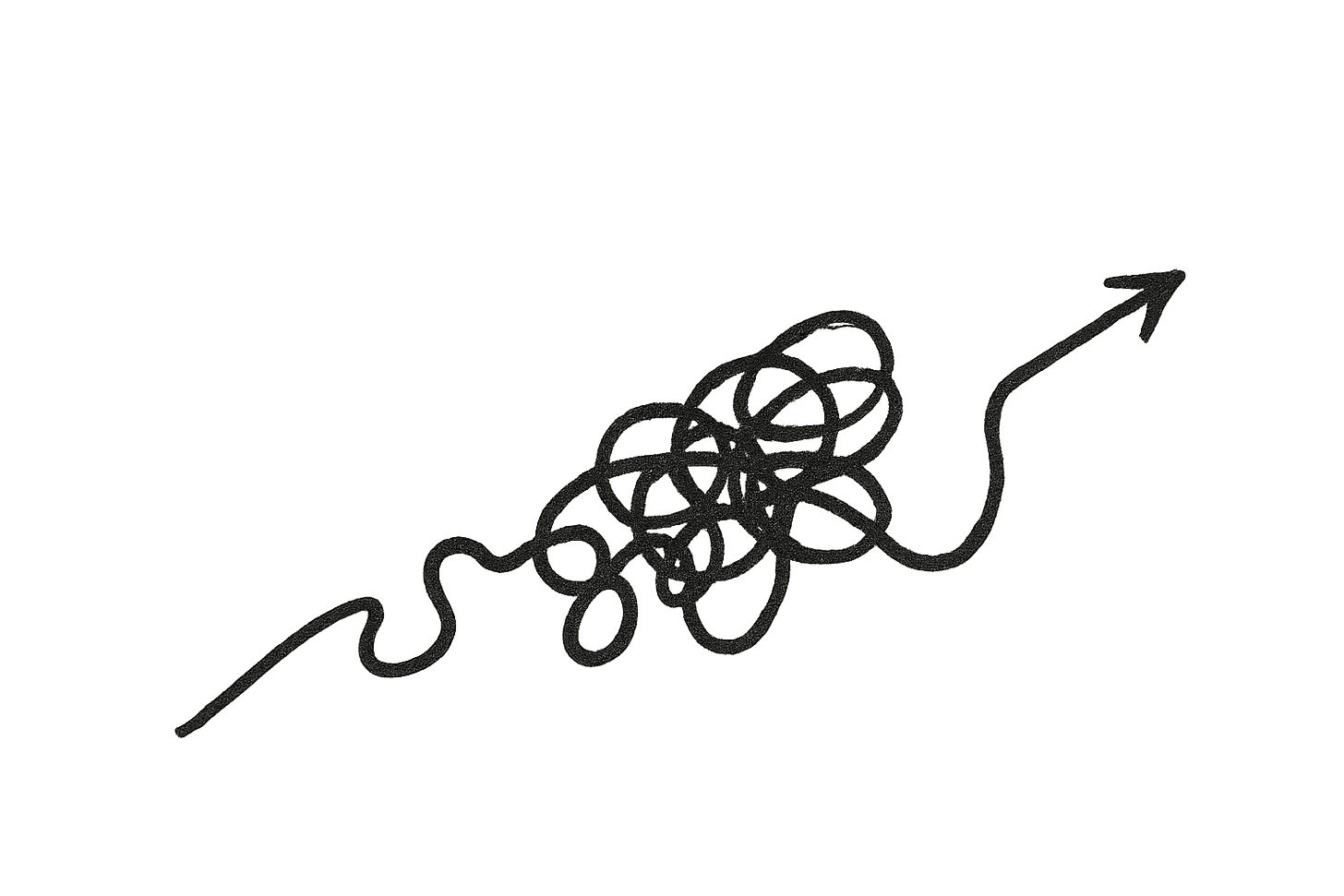

The Shape of Progress

A straight line is comforting. It’s predictable, easy to plan around. But a crooked one — full of loops, stalls, and detours — feels threatening. It creates uncertainty, and with it, a loss of control.

Our brains aren’t built to love that mess. They’re wired to make sense of the world through neat sequences. Memory itself isn’t a recording; it’s a reconstruction. When we look back, the brain edits out the false starts and dead ends. What we remember is a highlights reel — a clean, linear story that never really happened that way.

Stories, our most powerful tool for making sense of experience, follow the same script: beginnings, middles, and ends. Cause → effect → resolution.

And the systems we grow up in reinforce the illusion. Schools, workplaces, cultural myths—all of them push us toward straight paths: grades → college → job → promotion → retire. It’s society’s craving for order over chaos.

So when we face the real, messy shape of progress, it can sometimes feel like failure.

You think each piece will be better than the last. That publishing will bring more recognition each time. That sitting down to write will bring more clarity with every attempt.

But if you’ve lived long enough, you know nothing worthwhile moves in straight lines. And writing is no exception.

One day: silence. The next: a reply that makes your week. Another: a piece spreads further than you imagined. Then back again to just a few likes.

It may feel like confusion, but it’s simply the shape of progress.

The Roots of Voice

I’ve gone from zero to one a few times in my life. In the middle of the chaos and uncertainty, two things always prove essential:

Endurance and release.

The blows will come. But if you keep moving, the highs eventually arrive. Progress isn’t linear; it’s the commitment to continue that makes things fall into place. As George Saunders puts it: “We have to learn to honor our craft by refusing to be beaten, by remaining open, by treating every single thing that happens to us, good or bad, as one more lesson on the longer path.”

But endurance alone isn’t enough. Pile on too many expectations and the distractions will sneak in, pulling you away from what matters most.

In any writing project, my one non-negotiable is to write and publish consistently. Everything else—audience growth, monetization, networking—comes later. The shiny objects will always be there, whispering that if I just give them a try, results could come faster. That I could achieve more. My job is to let them pass without pulling me off course.

That same release has also to extend into the writing itself: letting go of processes that no longer serve me, of topics that might draw attention but don’t fit my voice, of readers I thought I was writing for but who were never truly my audience.

The path is always being dismantled and rebuilt.

This is the work every writer must go through. Me. You. George Saunders. There’s no skipping it if you want to find your voice and make the contribution only you can bring.

At first, going from zero to one feels intimidating. And yet it’s also the most generous phase of the journey: the time to experiment without pressure, to fail without consequence, to discover what you really mean before the world is watching.

Later, when the noise inevitably arrives, you may find yourself longing for that silence again—when the only expectations were your own.

Gianni, you have just pointed to something that led our rather famous Writers Week here in South Australia to be cancelled this year. An Australian writer of Palestinian origin was disinvited, and it created an uproar. Over 180 writers withdrew in protest, leading to the cancellation of the event and the resignation of the board. This took place weeks after a mad killing spree by a man and his father of Jewish people on Bondi Beach in Sydney. Committee-think in your words, rotted from within, from excessive risk-management predicated on race, trying to kill (stifle) freedom of speech. The board had no writers or artists on it at all. Your insights never fail to amaze me.

Thank you for sharing this while I wait for the first letter. I’ve shared it with my daughter who is a writer knowing she will also be encouraged as I was. I love your voice of encouragement. This letter moves the writer within to action as I needed to pick up my pen once again! Thank you!