The Prometheus Directive

How the platforms trained us to crave junk content — and what happens when AI takes over the menu.

“We’re ready to initiate Phase Two of The Prometheus Directive,” John Bremmer announced—looking down the long, sleek table at the four faces staring back at him—three men in dark suits, one woman in a cream blazer.

Lewis Clark, silver-haired, leaned forward. “Now that Eleanor Ashford has joined us,” he said, nodding toward her, “perhaps you could bring her up to speed.”

“Of course.” Bremmer moved to the whiteboard, and in slow, deliberate strokes wrote: Phase One.

“To understand Phase Two,” he said, turning back to the table, “we have to start at the beginning.”

His gaze locked on Ashford.

“How much of our revenue do we share with creators today?”

“Fifty-five percent,” Ashford replied instantly, eyes fixed on his.

“And what if”—Bremmer’s voice lightened, almost playful—“that number was zero?”

She frowned. “We wouldn’t have any creators.”

“True,” he said, nodding once. “And without them?”

“No audience. No money.”

“That’s the current equation.” He took a step closer. “But it changes after Phase Two.”

Ashford folded her arms. “Go on.”

“Picture a city where every corner, every block, every street serves only McDonald’s. To eat something healthy, you’d have to drive thirty minutes and pay double the price.”

“I’d probably eat a lot more McDonald’s,” Ashford said flatly.

“And after months?”

“I’d get used to it.”

“Exactly.” Bremmer’s eyes gleamed. “And if suddenly I invited you for a proper meal?”

“I’d probably have lost my taste for it.”

“That,” Bremmer said, tapping the whiteboard with his knuckle, “is Phase One. The algorithm floods the feed with fast-food content—cheap, addictive, everywhere. Then we give creators the tools to mass-produce it. We lower the cultural bar so gradually, no one notices the change.”

Ashford tilted her head. “So what’s Phase Two?”

Bremmer paused, then turned back to the board and wrote in block capitals:

AI-GENERATED PERSONALITIES.

“They’ll dominate the feed,” he proclaimed.

Ashford’s voice slowed. “But what about the creators? Won’t they push back?”

“Not if we give them the product first. Roll it out as a feature. Boost anyone who uses it. Offer exclusive tools only available with an AI face. They’ll teach each other how to use it, and how to profit from it.”

Ashford’s eyes narrowed. “So when you launch your own characters…”

“They’ll be playing a game they can’t win,” Bremmer finished for her. “Then it’s only a matter of time. No creators. One hundred percent margin. No demands from influencers who think follower count equals leverage.”

Clark finally spoke, his gravelly voice cutting in. “We basically own the narrative. Every headline. Every trending topic. Advertisers will dance to our tune. Politicians will… stay cooperative.”

Bremmer’s smile was now as sharp as the plan itself. “And with that, we’ll have everything we need to mold the world into what it should be.”

Fortunately, this isn’t a real story.

And not even something Huxley or Orwell has written.

But look around for a moment and ask yourself:

How far-fetched does it really seem?

Phase One

By the mid-2000s, Facebook had tapped into one of the most powerful levers in business: the ability to shape human behavior through technology.

Publicly, they called it “growth.” Privately, the real engine was habit formation — learning how to make people return, scroll, click, and share without thinking. Every new feature, from News Feed to photo tagging, wasn’t just about connection. It was about conditioning.

In 2007, Facebook opened its platform to outside developers, inviting anyone to ride the same wave of engineered engagement.

That same year, Stanford researcher BJ Fogg launched what became known as The Facebook Class. Fogg had spent years studying persuasion in technology, and he’d reduced it to a deceptively simple formula:

Behavior = Motivation + Ability + Prompt.

To get someone to act, you had to deliver all three: give them a reason to act (motivation), make it easy (ability), and hit them with the right trigger at the right time (prompt).

Many of his students saw Facebook’s new developer platform as the perfect laboratory to test the model at scale.

And almost overnight, their apps tapped into Facebook’s viral loops and spread to millions.

That was the moment behavioral science leapt from academia into the bloodstream of Silicon Valley — and some of those students would go on to build the products that defined the next decade. Among them was Mike Krieger, who co-founded Instagram.

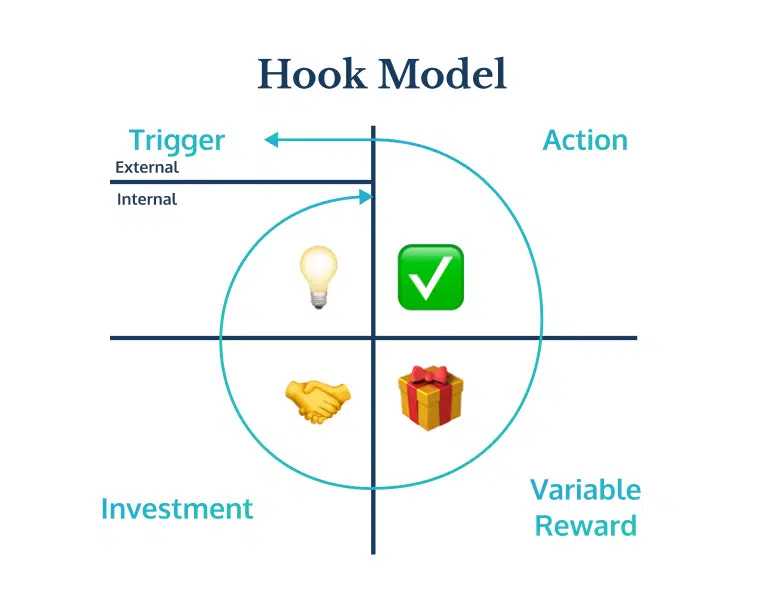

While others built the platforms, one student, Nir Eyal, took Fogg’s principles and shaped them into the now-famous Hook model:

The most powerful lever in the Hook model was the variable reward — a form of intermittent reinforcement Eyal compared to a lottery.

Every time you pull the lever on a slot machine, the uncertainty is what keeps you playing. Sometimes you win, most times you don’t — but the unpredictability makes the next pull irresistible.

Social platforms took that same mechanism and digitized the casino. Refresh your feed, check your notifications, open your DMs — most of the time, nothing. But every so often, the jackpot: a viral post, a like from someone important, a message you’ve been waiting for.

The logic was straightforward: keep people hooked, and “growth” will follow.

But as algorithms grew more sophisticated, they found an even faster route to attention — hollow, high-calorie content.

Give people an endless outlet to switch off their brains, feed them just enough stimulus to keep chasing the next hit, and they’ll lose track of time.

So tuned for maximum engagement, the feeds began serving more and more processed content — quick jolts of outrage, provocation, lust, or envy. The “fine dining” of thoughtful, original work still existed, but for most users, it had been pushed to the far edges of the map.

On paper, Fogg’s formula and Eyal’s loop were neutral. In the hands of growth-obsessed platforms, they became the assembly line for junk content.

And here’s what the platforms counted on — and got right: over time, people adapt. They accept the processed feed as normal. They lower their expectations. Their appetite for anything richer goes numb.

Once your palate adjusts, you stop seeking new flavors. That’s when the loop collapses into an echo chamber — serving the same opinions, the same emotional triggers, daily.

It’s like living in a city where every street corner only has McDonald’s, and every time you order, the menu adjusts just for you — saltier fries if that keeps you coming back, more sugar in the shake if that makes you crave more. Eventually, you stop looking for healthy food. You start believing McDonald’s is all there is.

What began as a breakthrough in behavioral science ended up shaping a digital diet that leaves us full — but never nourished.

Phase Two

The Chicago Sun-Times recently published a “Summer Reading List for 2025.” It looked like any other seasonal article, except for one glaring issue: the first ten books didn’t exist. They were entirely fabricated by AI, and no one caught the mistake before it went live.

I know it sounds absurd. But if there’s a silver lining, it’s this:

There was still a trace of human accountability in this story. The mistake traveled the internet, leading the Chicago Sun-Times to acknowledge the error in public.

But what happens when that human layer hides itself behind an AI character?

When AI becomes the creator AND the messenger?

Take Aitana López, for instance. A pink-haired Instagram influencer with hundreds of thousands of followers.

She isn’t real. She was created by Rubén Cruz, an agency owner tired of working with real models.

“We did it so that we could make a better living and not be dependent on other people who have egos, who have manias, or who just want to make a lot of money by posting.”

Or consider the case of The Velvet Sundown, a band that appeared in mid-2025, releasing two albums — Floating on Echoes and Dust and Silence — and racking up hundreds of thousands of Spotify streams within weeks. Their single Dust on the Wind even hit No. 1 on Spotify’s Viral 50 in Britain, Norway, and Sweden.

But none of it was real. After weeks of speculation, The Velvet Sundown revealed in their Spotify bio and on social media that the band had been entirely generated by AI.

I thought these were rare cases, the kind you could count on one hand, but a quick search pulled up wild headlines everywhere.

Now imagine a tool for writers to create their own AI persona. You choose the topics, define the style, fine-tune variables like tone and references—then set it loose in the world. Forget writing, just calibrate. The platform feeds you the data, and you make the calls: “Looks like the controversial stories are hitting hard. Let’s keep tapping into that.”

Whether you imagine it or not, there are already a few platforms thinking ahead.

In 2025, Meta announced it would be creating an AI product that helps users create AI characters on Instagram and Facebook, allowing these characters to have bios, profile pictures, generate and share "AI-powered content" on the platforms. Bot accounts managed by Meta began to be identified by the public around on January 1, 2025, with social media users noting that they appeared to be unblockable by human accounts and came with blue ticks to indicate they had been verified by Meta as trustworthy profiles. - Wikipedia

It’s pretty clear that the line between “real” and “synthetic” is dissolving.

And the question that lingers is: Without accountability, whose voices can we trust?

When AI characters begin to outnumber us, what happens to our culture—and to the internet as we know it?

The Modern Currency

When food production became industrialized in the mid-20th century, processed foods, refined sugar, and hydrogenated oils exploded in popularity.

For decades, the focus was on abundance and convenience rather than nutrition. And the toll was clear: rising obesity rates and a surge in heart disease across industrialized nations.

It took years — and cultural moments like Fast Food Nation (2001), Supersize Me (2004), and Food, Inc. (2008) — before people began to think critically about the quality of what they were eating.

We eventually learned to question what we were feeding our bodies.

But perhaps now it’s the time to take seriously what we let into our minds.

Whether or not there’s a Bremmer, Ashford, and Clark plotting behind closed doors, in the end we control only one thing:

Our Attention.

Attention is the modern currency — traded every second you’re online.

Platforms buy it from you at a discount — a click here, a scroll there — and resell it at a premium to advertisers. But its real cost isn’t measured in money. What you give attention to shapes your taste, your thoughts, even your sense of self. Spend it carelessly, and someone else will decide what fills your mind.

It’s like walking into McDonald’s three times a day: sooner or later, you’ll order a burger. Give it time, and the burger comes with fries. Then Coke. Before you notice, that’s your daily diet.

And as you grow accustomed to bad taste, your appetite goes numb.

You pick up Dostoevsky and your mind drifts; your eyes slide back to the phone. You reread the same line three times. The apps are still there, one tap away, calling you back to the feed.

But if you resist, if you refuse to undersell your attention for content engineered to keep you empty, you begin to reclaim your agency.

Simone Weil calls attention “the rarest form of generosity.” And that generosity has to be extended not just to other people, but to the ideas and works we let into our minds. Taste isn’t some gift you’re born with; it’s shaped, slowly, by what you give your full attention to.

As a writer, I’m acutely aware that I’m either adding to the pile or inviting readers to sit at the table for a proper meal. And the quality of that meal is set long before I serve it—shaped by where, and how, I spend my attention.

In a city full of McDonald’s, a proper meal can seem absurd. But if I keep showing up, I trust a few curious minds will find their way to the table.

And when they do, they may rediscover an appetite they didn’t know they’d lost.