What Tarantino Can Teach Nonfiction Writers About Suspense

How to Write Like There’s a Bomb Under the Table

It’s a quiet morning on Monsieur LaPadite’s farm. He’s bent over a tree stump, bringing the axe down in slow, deliberate arcs. Nearby, one of his daughters hangs a sheet out to dry. Then, from the distance—an unsettling hum.

German soldiers are coming.

So begins the long, haunting opening scene of Inglourious Basterds.

Tarantino is known for stylized violence and eccentric characters, but in this scene, he offers something subtler: a masterclass in holding tension.

For 17 pages—nearly 20 minutes of screen time—Colonel Landa interrogates LaPadite to uncover whether he's hiding Jews on his farm.

At first, we only suspect that LaPadite is hiding something. But then, Tarantino drops the camera below the floorboards and we see the truth: a Jewish family, hands clutched over their mouths.

That’s the moment the bomb is planted.

From that point on, every line of dialogue carries a weight they never name, but we feel it. We’re not just watching. We’re trapped inside it, breath held, waiting for the explosion.

In an interview with Charlie Rose, Tarantino offered a glimpse at what he’s doing:

The suspense is a rubber band, and I'm just stretching it and stretching it to see how far I can stretch. As long as that rubber band can stretch, the longer the scene can hold, the more suspenseful it is. So you want to stretch it until the rubber band breaks.

That metaphor stuck with me—but it crystallized when I heard Hitchcock describe the same principle with a different image:

Talking about baseball, whatever you like. Five minutes of it, very dull. Suddenly a bomb goes off. What the audience has? Ten seconds of shock. Now take the same scene and tell the audience there's a bomb under that table, and will go off in five minutes. The whole emotion of the audience is totally different.

And it got me thinking…

Could this same technique work in nonfiction?

If so, who’s doing it—and how?

Tim Urban's Ticking Bomb

In The AI Revolution: The Road to Superintelligence, Tim Urban opens with an unsettling simple question:

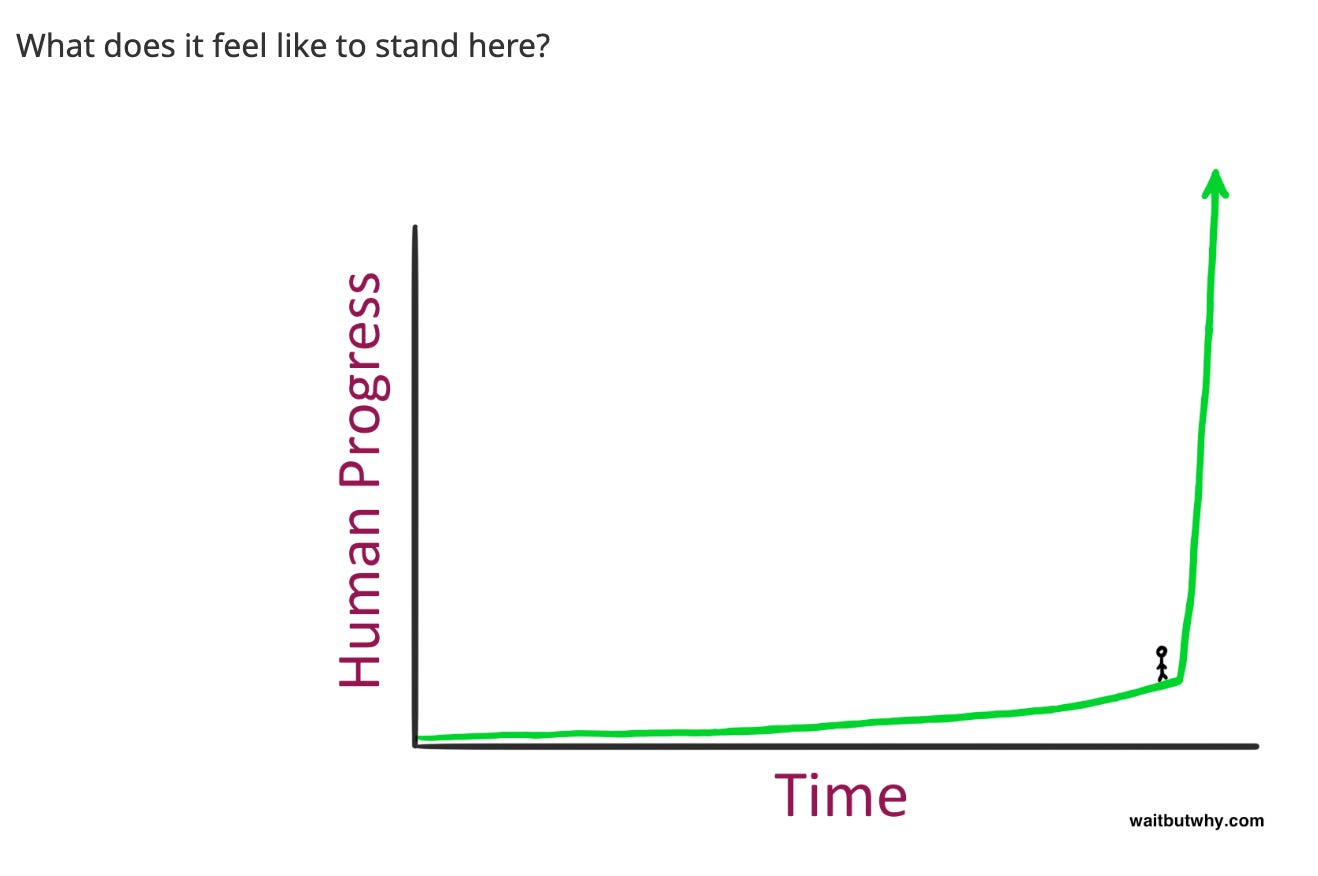

That question is the bomb. It points to a future we’re rushing toward—faster than we’re prepared for. But instead of answering it, Urban delays detonation.

He takes us on a sweeping journey: back from the present, through 1750, past 12,000 B.C., all the way to the era of hunter-gatherers. Each turn adds context. Each stop raises the stakes.

Along the way, we begin to grasp the idea at the heart of it all: the Law of Accelerating Returns—how human progress keeps compounding, moving quicker and quicker as time goes on.

Just when it seems he’s ready to circle back to the question, Urban takes one final detour, addressing the skepticism that always arises when we talk about the future.

So then why, when you hear me say something like “the world 35 years from now might be totally unrecognizable,” are you thinking, “Cool….but nahhhhhhh”? Three reasons we’re skeptical of outlandish forecasts of the future:

By the time he finally returns to the question, we’re stretched to the edge of understanding—ready to face the implications of the AI revolution and where it might lead us.

Anne Helen Petersen's Ticking Bomb

In How Millennials Became the Burnout Generation, Anne Helen Petersen opens with a subtle but high-stakes signal: this isn’t just about feeling tired. It’s about a generation burning itself to the ground.

But she resists the urge to spell it out outright.

Instead, she begins with the mundane: putting off errands, slogging through to-do lists, folding laundry that never seems to end. Then, layer by layer, she zooms out—economic expectations, the achievement trap, the relentless pressures of online performance.

As she helps us piece together the puzzle, the tension quietly builds. The bomb keeps ticking beneath the surface until she finally names it:

"All of this optimization—as children, in college, online—culminates in the dominant millennial condition, regardless of class or race or location: burnout."

The realization lands hard because we’ve lived the buildup.

By the time she defines the condition, we’ve already felt it. We've traced its causes, seen it in our own lives.

Burnout is no longer just a buzzword we toss around.

It’s a diagnosis we can understand—emotionally, intellectually, and viscerally.

George Saunders' Ticking Bomb

In his GQ essay The New Mecca, George Saunders gives voice to a question many were quietly asking in 2005:

What Dubai is all about?

But rather than offer a straight answer—or build a tidy argument—he invites us on "a guided tour through steroidal capitalism, world revolution, and the finest hotel rooms money can buy."

Saunders traces Dubai’s dizzying transformation—from a cluster of mud huts to “the Vegas of the Middle East.”

We follow him through luxury villas, a Jeep ride into the desert, an Iranian cab driver’s spiritual confession, a frustrating hotel credit card hiccup, and, finally, the labor system powering it all.

Along the way, he challenges our expectations. When he reaches the topic of consumerism, you anticipate a moral critique. Instead, he offers something startlingly sincere:

I have been wrong, dead wrong, when I've decried consumerism. Consumerism is what we are. It is, in a sense, a holy impulse. A human being is someone who joyfully goes in pursuit of things, brings them home, then immediately starts planning how to get more.

As the story unfolds, the question lingers: Where is this going to land?

The narrative wanders—but the wanderings matter. Every digression deepens the dissonance. Each detail stretches the rubber band a little further.

Then, after nearly 10,000 words of playful observation, comes the snap:

In all things, we are the victims of The Misconception From Afar. There is the idea of a city, and the city itself, too great to be held in the mind. And it is in this gap (between the conceptual and the real) that aggression begins. No place works any different than any other place, really, beyond mere details.

The universal human laws—need, love for the beloved, fear, hunger, periodic exaltation, the kindness that rises up naturally in the absence of hunger/fear/pain—are constant, predictable, reliable, universal, and are merely ornamented with the details of local culture. What a powerful thing to know: That one's own desires are mappable onto strangers; that what one finds in oneself will most certainly be found in The Other.

The bomb doesn’t explode so much as echo. In the end, Saunders doesn’t offer an answer. He offers complicity.

Planting the Ticking Bomb in Your Work

As you’ve seen, the ticking bomb in nonfiction can take many forms:

A question that lingers—uncomfortable, unanswered, and impossible to ignore.

A silent ache a generation carries without knowing why.

A city that looks like the future—but no one can quite say what that future means.

In each case, the writer doesn’t jump to defuse the bomb. They reveal it early, then take us on a journey. A long one.

With every paragraph, they add weight—more context, more contradictions, more story. Each one stretches the rubber band tighter. Builds anticipation. Makes us crave for resolution.

And I’ll be the first to admit—it’s not easy.

In my own writing, I often feel the pull to explain too soon—to offer clarity before readers scroll away. But the best essays remind me that tension isn’t the enemy. It’s one of the writer’s greatest allies.

So next time you write, ask yourself:

What’s the bomb under the table?

What’s truly at stake here? What truth is hiding beneath the surface? And how long can I let the tension stretch?

Maybe it’s a personal story with a reveal you’re not ready to give away just yet. Or a complex idea that needs room to breathe. Or a thought-provoking question you plant in the opening—then hold off answering until the very end.

Whatever form it takes, don’t rush. Don’t relieve the tension too early.

Let your readers sit in the uncertainty. Hold them there. Make them lean in, waiting for what's coming.

Because when the bomb finally goes off...

It won’t just inform.

It will hit home.

And stay with them for a long time.

A quick shoutout to Michael Tucker—his video on the opening scene of Inglourious Basterds sparked this whole essay. If you’ve got a few minutes, it’s absolutely worth a watch.